reden über schreiben über film(e): #11 armond white (engl version)

Von Oliver Nöding // 3. September 2014 // Tagged: featured, Interview // 1 Kommentar

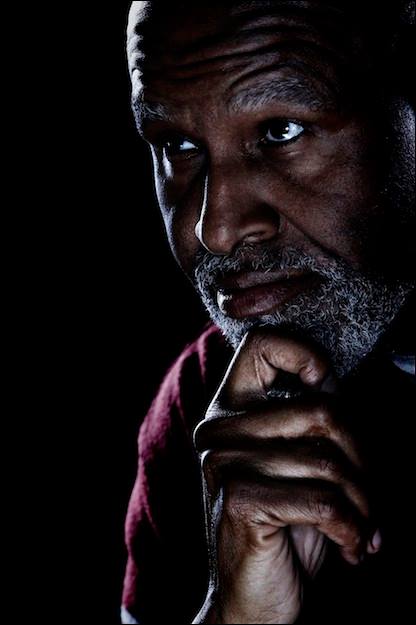

Not many film critics incite controversial discussion like Armond White. Born 1953 in Detroit as the youngest of seven children, the reviews of Pauline Kael inspired him to become a film critic. After graduating from Columbia University with a Master of Fine Arts degree he begun his long career, which led him from The City Sun to the New York Press. He is not only interested in film but also in pop music and pop culture in general and is author the books „The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture That Shook the World“, „Rebel for the Hell of It: The Life of Tupac Shakur“ and „Keep Moving: The Michael Jackson Chronicles“. Armond White’s reviews are strict, often polemic and always polarizing. The rise of amateur film criticism and nerd culture are common targets of him, as are colleagues, who nowadays often function as mere advertising instruments and have arranged themselves with the status quo instead of supporting art. Then of course there are the films: White doesn’t care for consensus and he sharply criticizes films that are commonly celebrated as masterpieces, like THE DARK KNIGHT or GRAVITY, on the other hand being one of the rare voices to praise the works of Adam Sandler, Eddie Murphy, Jason Statham or Michael Bay. His role of the lone wolf of film criticism gained him many detractors: Googling his name, you will find articles denouncing him as „contrarian“, a lunatic or some kind of joke but also those that pay him their deeply felt respect. An inactive blog called „Armond Dangerous“ analyzed every single review of him, meticulously collecting every factual mistake, stilistic and argumentative inaccuracy. (White’s Wikipedia entry actually offers a good overview about the whole critical discourse on him.) White’s annual „Better-than-List“ is a cause for active online discussion, as he offers his mostly unpopular alternative to overhyped and generally beloved films. Comments under his reviews show a widening gap between his avid supporters and haters. Whatever you may think of him, you certainly cannot criticize the man for a lack of true passion and love for his medium. His colleague Owen Gleiberman once compared him to Lester Bangs and Paulin Kael, saying: „He parades his unruly, belligerent perceptions like hardcore psychological rock & roll.“

Not many film critics incite controversial discussion like Armond White. Born 1953 in Detroit as the youngest of seven children, the reviews of Pauline Kael inspired him to become a film critic. After graduating from Columbia University with a Master of Fine Arts degree he begun his long career, which led him from The City Sun to the New York Press. He is not only interested in film but also in pop music and pop culture in general and is author the books „The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture That Shook the World“, „Rebel for the Hell of It: The Life of Tupac Shakur“ and „Keep Moving: The Michael Jackson Chronicles“. Armond White’s reviews are strict, often polemic and always polarizing. The rise of amateur film criticism and nerd culture are common targets of him, as are colleagues, who nowadays often function as mere advertising instruments and have arranged themselves with the status quo instead of supporting art. Then of course there are the films: White doesn’t care for consensus and he sharply criticizes films that are commonly celebrated as masterpieces, like THE DARK KNIGHT or GRAVITY, on the other hand being one of the rare voices to praise the works of Adam Sandler, Eddie Murphy, Jason Statham or Michael Bay. His role of the lone wolf of film criticism gained him many detractors: Googling his name, you will find articles denouncing him as „contrarian“, a lunatic or some kind of joke but also those that pay him their deeply felt respect. An inactive blog called „Armond Dangerous“ analyzed every single review of him, meticulously collecting every factual mistake, stilistic and argumentative inaccuracy. (White’s Wikipedia entry actually offers a good overview about the whole critical discourse on him.) White’s annual „Better-than-List“ is a cause for active online discussion, as he offers his mostly unpopular alternative to overhyped and generally beloved films. Comments under his reviews show a widening gap between his avid supporters and haters. Whatever you may think of him, you certainly cannot criticize the man for a lack of true passion and love for his medium. His colleague Owen Gleiberman once compared him to Lester Bangs and Paulin Kael, saying: „He parades his unruly, belligerent perceptions like hardcore psychological rock & roll.“

Mr. White, first of all let me tell you that we are proud to have you answering our questions as part of our ongoing interview series. You are the second American film critic we interview and the first one who started long before there was internet and online film criticism. I would like you to start with telling us how you got started as a critic, what were your intentions, wishes, maybe dreams? What did you hope to bring to the table that you thought was missing?

There used to be terrific film critics in the American mainstream media and these were the ones who inspired me—Kael, Sarris, John Simon, Stanley Kauffman, James Agee, Arthur Knight, Judith Crist, Hollis Alpert, Bosley Crowther, Vincent Canby,Manny Farber and among academics there were Raymond Durgnant,Andre Bazin, Leo Braudy, Richard Griffiths and Kevin Brownlow. They defined the possibilities in writing film criticism. I can be a fan but I’m not a follower. I had to develop my own perspective—which I wanted to add to theirs as if to communicate and exchange ideas, a form of gratitude. By reading those pioneers, I learned to see movies their way but it became necessary to understand movies—and culture and life—as I experienced it myself. That’s what was missing.

Could you sum up what film means to you? Was there an initial cinematic experience that changed your view on film and life forever? What do you look for in film? And how do you approach it when you’re writing about it?

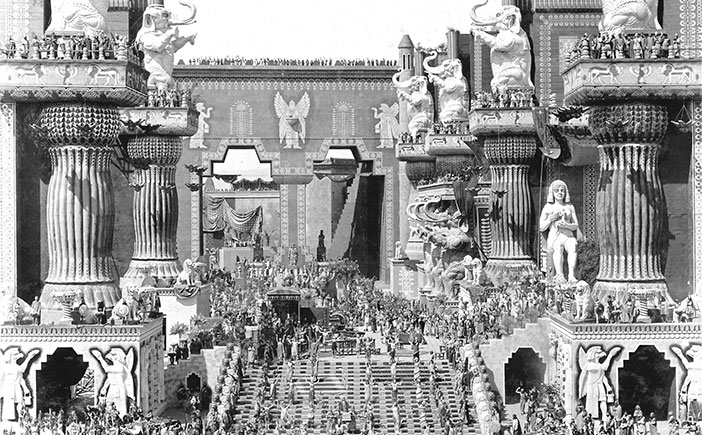

Movies always meant as much to me as popular music (having grown up in Motown and experienced that great musical achievement close-up). Music and Movies gave insight into the world and into humanity (human thought, aspiration, etc.). Film is great entertainment—a pleasure along with pop music— so I came to appreciate one along with the other. I’d alway s rather listen to great pop than watch a bad movie. But the visual excitement of film combines all the other arts magnificently. There are lots of landmarks that proved this to me from INTOLERANCE (D. W. Griffith, USA 1916) to LA PASSION DE JEANNE D’ARC (Carl Theodor Dreyer, Frankreich 1928) but those classics pre-existed my awareness. In my lifetime the French New Wave and Robert Altman’s films — especially CALIFORNIA SPLIT (Robert Altman, USA 1974) — defined the possibilities. That innovation, that beauty, that truth is what I always look for. When I find it—or don’t—the challenge is to make sense of it. To put it into context, to create the continuity of cultural and political and personal history.

INTOLERANCE (D. W. Griffith, USA 1916)

As someone who watches films professionally, how do you manage to “switch off” the critic in yourself when you watch a film for private amusement? Or don’t you switch off at all?

There’s never an „off switch“ unless you stop breathing, seeing, hearing. Everything you do goes into appreciating art and that’s a non-stop process.

When do you think did you become a “notorious“ critic? Was it a natural development that more and more people got irritated or even bothered by your reviews or was there a certain decision, some kind of conscious change of direction on your behalf? Is there a point in your career when you realized you had the talent to get a reaction from your readers?

Thank God I got started writing criticism before the Internet warped the minds of a new generation—and a changed society for-the-worst. I started with the sense that criticism ought to be challenging and always appreciated that (before the Internet) people read me that way. It’s only the Internet era that changed other peoples‘ notions of what criticism should be and began the idea of a „notorious“ critic. Before the Internet, readers liked new perspectives and ideas. After the Internet, the lock-step began. Criticism declined and the adolescent mob mentality took over when many people became afraid of having unpopular opinions and tried to conform to the mob. And writing for Black-owned and alternative media also helped develop a healthy sense of independence. Those publications—The City Sun and New York Press—catered to readers who questioned the status quo and opposed the mainstream. Now the Internet and TV encourages people to think alike or else to be non-thinking consumers. This intellectual decline creates readers who are easily offended by IDEAS.

THE TRANSPORTER 3 (Olivier Megaton, Frankreich 2008)

In your reviews you often stress the importance of Pauline Kael – to your own development as a critic and film criticism as a whole. She was not only known for her insightful writing but also for her willingness to attack directors and actors, to measure them with high ethic standards and call them out when she thought they failed to meet them. You seem to be keeping up that tradition. You are one of the few critics who criticize film not only as commercial product but as a contribution to culture as a whole. Do you fight a losing battle or are you comfortable with your position as an outsider or even outcast?

Thoreau said any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a Majority of One and that’s my feeling, too. Fact is, the mainstream „majority“ is simply the mob, class dopplegangers who come from the same socioeconomic and political backgrounds. They think the same and lack originality but they are not the world; they simply comprise the majority of media. They have no premium on thinking or feeling. The most brilliant people I know from film school and elsewhere never made it as film critics so I am not in the least intimidated by other reviewers. As with Pauline Kael, the outsider or outcast question is not my concern.

Your reviews are often harsh and personal in their critique. You treat films you don’t like as if you feel personally annoyed by them. And you seem to confront every film the same, regardless if it’s high cinema or a popcorn movie. One would never read a phrase like “it’s good for what it is“ in one of your reviews. Do you think that’s missing in film criticism: The belief that every film can contribute something positive to society and culture instead of just cater to a certain focus group and keep them shallowly entertained for 120 minutes?

You better believe it. Every film has to stand next the best that has been done. Otherwise we are all dupes. My criticism is never a personal disparagement but I do take art seriously and take film criticism seriously. Replace „harsh“ with „honest“ because that’s how every critic should be.

You are somewhat notorious for what your distractors call “contrarianism“. They accuse you of deliberately objecting critical consensus. As far as I know, you got expelled from Rotten Tomatoes because people complained about you ruining the scores of what they thought were perfect films. And your colleague, the late Rober Ebert, went so far as to call you a “troll“. But instead of explaining or justifying yourself you keep actively widening the gap by writing your “Better-than-list“ at the end of the year. You certainly have fun teasing and challenging your opponents and playing the black sheep, don’t you?

Being a film critic can be fun—as well as hard work. Being Rotten Tomatoes is just juvenile idiocy, a way of nullifying real film criticism.When websites and cliques „expel“ me, it’s a sign of the culture’s weak and cowardly inability to engage in discourse. If there is such a thing as „contrarianism,“ then please define the conformity and group-think that it’s contrary to.

Somewhere on the internet I read from someone who met you personally and was really surprised to find out that you are not the cranky and cantankerous person you seem to be in your reviews but really pleasurable and talkative. Is your authorial voice just an act to bring your – important – point across, to incite discussion and maybe even evoke dissent, to resuscitate the discussion of film as a whole?

A critic needs a strong voice. A gentleman has manners.

There have been some controversies around you in the last couple of years. You were expelled from the New York Film Critic Circle after allegedly having heckled award winner Steve McQueen. Do you want to say something about it?

I never heckled McQueen and had no reason to. My 12 YEARS A SLAVE review spoke powerfully enough—so powerfully the Circle’s cowardly members apparently felt compelled to lie about me and embarrass themselves.

12 YEARS A SLAVE (Steve McQueen, USA 2013)

You not only criticize film but also the current state of professional film criticism. It’s obvious that film criticism has become a mere marketing tool. Many film critics are nothing more than peddlers of product, who lack not only knowledge of film history or technique but any idealism, any insight in the importance and meaning of art and culture. This development seems to be connected to the big studios putting out franchises instead of films. And of course to the larger context of postindustrialism and neoliberalism. Where is this going to end? And: Is it? Are there any present critics you would recommend to our readers?

Isn’t it obvious that the media industry is also producing reviewer „franchises“? Ad quotes and aggregate websites now do the work of publicity departments. And the Internet is largely a wilderness of amateurs—without the love and rigor that word should imply.

As someone who keeps a blog and tries to bring an alternative perspective on films I think are misunderstood or neglected, I don’t quite know what to make of your attacks on amateur film criticism. On the one hand you’re right: there’s way too many people online who offer nothing valuable besides their uneducated opinion. On the other hand I think blogging is a chance for independent film criticism and it brings an idealism and enthusiasm that seems to be missing otherwise. Tell me that you agree at least a bit.

I am responding to you respectfully, aren’t I? believe in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment guaranteeing freedom of speech. I despair of Internetters who don’t take film criticism or film scholarship seriously and so are childishly offended when this obvious fact is pointed out. Can bloggers engage me in a serious way? Ad hominem attacks on me are not a respectable response to the ideas I express; it reveals the Internetters as unworthy.

You seem to be the only vocal black critic – at least that’s the impression a German reader has from the distance – and you’re especially critical of Afro-American directors: the aforementioned Steve McQueen, Tyler Perry and Spike Lee have all gotten into your crosshairs. Can you summarize what you miss in contemporary black cinema?

When I regularly reviewed hip-hop music, one of the genre’s popular sayings was „I’m not new to this. I’m true to this.“ I write about many excellent black filmmakers and good to great films about black life. THE COLOR PURPLE (Steven Spielberg, USA 1985), BELOVED (Jonathan Demme, USA 1998), AMISTAD (Steven Spielberg, USA 1997), MR. 3000 (Charles Stone III, USA 2004), NEXT DAY AIR (Benny Boom, USA 2009), THE SKINNY (Patrik-Ian Polk, USA 2012), TAKERS (John Luessenhop, USA 2010), BABY BOY (John Singleton, USA 2001) and many, many others. Most critics don’t bother; they only write about big-budget, well-hyped „black“ movies.

THE SKINNY (Patrik-Ian Polk, USA 2012)

Film historian Donald Bogle has done important work in opening discussion on Afro-American film history. Still, there remains a lot of ground to cover. How much has happened in regard to acknowledging the meaning of Afro-American film for US-American film culture as a whole?

Is Bogle still writing? Little has changed from the tie Bogle published his first book besides what Harvey Weinstein calls „The Obama Effect“ which was merely a way to pretend race doesn’t matter as long as white Liberal sanctimony is preserved.

Is it even possible for white critics to discuss Afro-American cinema without stepping into the pitfalls of racism or coming across as condescending and imperialistic? Is it a discourse that has to be spearheaded by Afro-American critics and directors?

Critics—white or otherwise—should first attempt to avoid the pitfalls of racism and condescension. Few bother to try as proved by their praise for Obama Effect movies.

When I asked Spike Lee whether he views himself as one of the last representatives of the New Black Cinema he answered “Of what?!” His outlook on the present state of Afro-American cinema is utterly pessimistic. Do you agree that there are no real talents since the careers of Townsend, Matty Rich and others have ended and others went in a new direction?

I hope Germany and the rest of Europe and the world has seen BELOVED, NEXT DAY AIR, MR. 3000, the NOAH’S ARC movies and many others. Black filmmakers has moved way beyond Townsend and Matty Rich. Start with THE COLOR PURPLE, BELOVED and AMISTAD.

BELOVED (Jonathan Demme, USA 1998)

New Black Cinema was a discoursive and ideological movement. In just a couple of years an impressive number of interesting films were made. Its discontinuation is a bitter loss. Which role did reception from both audiences and critics play in its demise?

Over time THE COLOR PURPLE has gained an enormous and appreciative audience—it’s only racist film critics who refuse to acknowledge it. I repeat, start with THE COLOR PURPLE, then AMISTAD and BELOVED.

Filesharing has unearthed parts of film history that have been obscured in the last decades. The films of Ousmane Sembene, Satyajit Ray, animation films from Poland, Austria or Japan, the Yugoslawian Black Wave, the Polish film school movement: You can watch whole movies you never knew existed a couple of years ago on streaming portals like Youtube, with user provided subtitles. It seems to be an important part of cinephilia. Yet magazines don’t seem to recognize and address this change – at least in Germany. What do you think about these changes in film reception?

It’s always good to see obscure movies any way you can but the big screen is best. Anything else is not cinema but television.

There’s a drastic change in cinema going on these days. German cinephiles witness the death of 35 mm projection and the advent of digitalization. Some 35 mm copies get transferred to digital being destroyed in the process, others will be lost forever. Many German journalists see a lack of respect towards film culture in this approach especially in comparison to other forms of art, which are more widely respected over here. What is your opinion on this development? What’s the difference between watching film on film material and watching a digital copy? How is this topic discussed in the USA?

Watch movies however you can but seeing them on the big screen—as originally intended—will always be preferable. It makes a difference like seeing paintings in museums rather than book or Internet reproductions.

You don’t seem to be too fond of genre films – horror, action, science fiction – and generally opposed to the graphic display of violence in film. Quentin Tarantino is just one director you keep criticizing for his style. On the other hand you have championed „genre films“ like THE TRANSPORTER 3 (Olivier Megaton, Frankreich 2008), TRANSFORMERS: REVENGE OF THE FALLEN (Michale Bay, USA 2009) or RUNNING SCARED (Wayne Kramer, USA 2006) just to name a few. What does it take for a genre movie to transcend its boundaries and become art?

You just said it: transcend the genre’s boundaries and become art. That’s what DePalma used to do, same as Altman, Welles, Renoir, Antonioni, Dreyer, David Lean and Alfred Hitchcock and Luis Bunuel.

What would be better for cinephilia as a whole: If all of a sudden there would be a tremendous interest in African classics by Sembene, Mambety or if more people would start to treat a film like TRANSFORMERS (Michael Bay, USA 2007) with the same amount of respect and thought they reserve for acclaimed classics or high art?

What’s more important: More attention for art or a revision of the term “Mainstream”? Sembene and Mambety face the same neglect as Robert Altman, Julian Hernandez, Terence Davies, Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou. Contemporary film culture needs to expand its interest to include the masters not just the trendily fashionable.

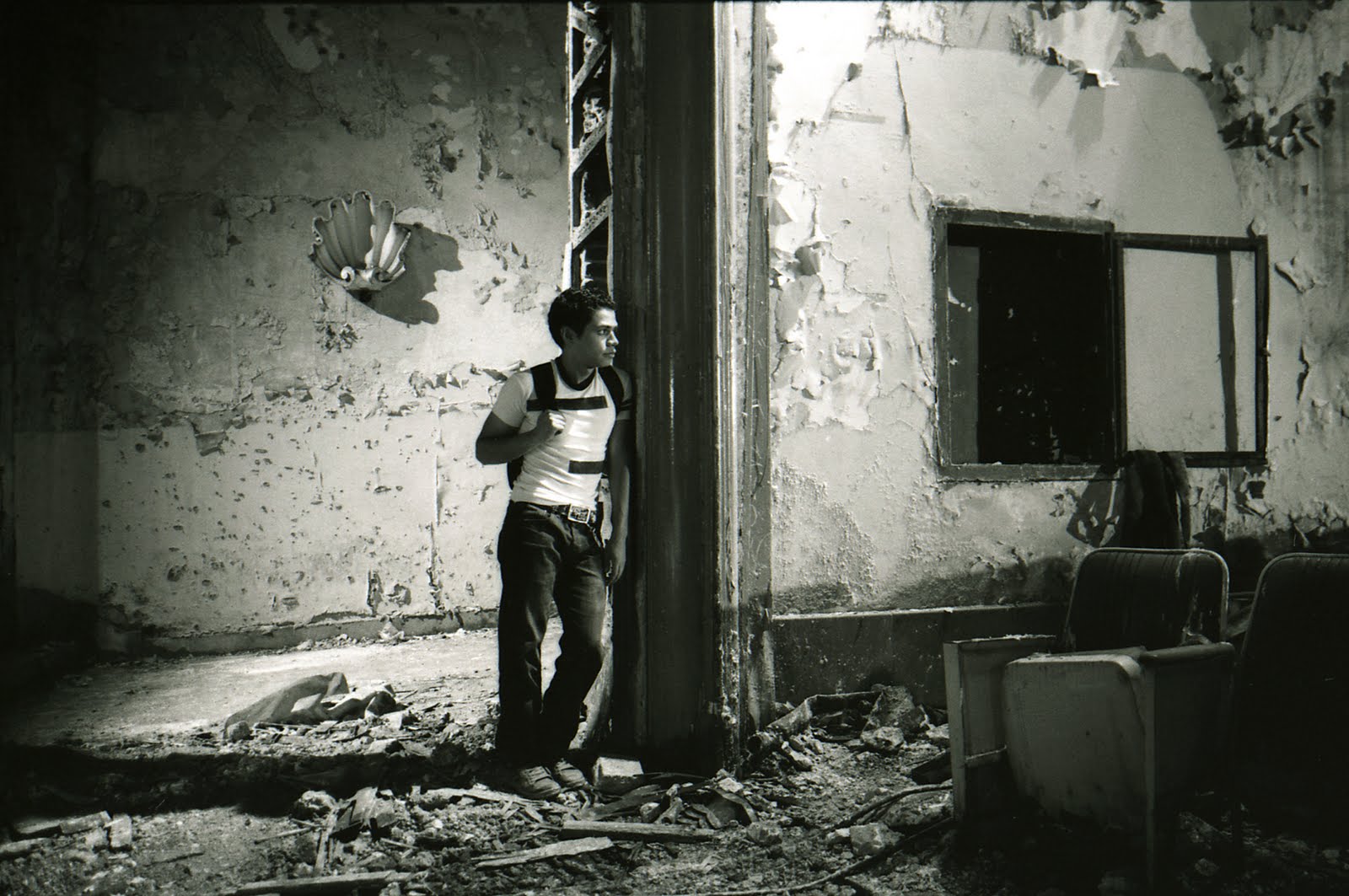

RABIOSO SOL, RABIOSO CIELO (Julian Hernandez, Mexiko 2009)

I first read of you when I was researching for a private Brian De Palma retrospective. What you said about him and his films, the fact that you defended him against the consensus, really spoke to me. I simply love his movies because they’re so rich and elegant, yet at the same time often funny and weird. Can you summarize what makes him special to you?

Your summary does the job. I congratulate you on your good taste. If you like DePalma Julian Hernandez—another erotic visionary—should appeal to you equally.

Another artist that you keep defending against the overwhelming majority of critics is Adam Sandler. Whenever he has a new film coming out, people almost queue up in order to trash him. I thought that GROWN UPS (Dennis Dugan, USA 2008) and its sequel GROWN UPS 2 (Dennis Dugan, USA 2013) were two of the most beautiful and original comedies in a long while, full of life, heart and atmosphere. What do you like about him and his films and why do you think he’s getting all that hate and ridicule?

American critics are in a tragic state of political and identity crisis—that’s why Adam Sandler and Eddie Murphy are routinely attacked and disrespected. They remind moviegoers of their own humanity and film critics are desperate to appear smart and elitist. But Sandler and Murphy are comic artists at their peak. Murphy and Sandler treat human experience with the personal honesty and grace of the greatest film artists yet never stop being funny. Critics who excoriate them are missing out and fooling themselves.

Finally, I would like you to give our readers three recommendations: Which (preferrably non-canonic) American films should they seek out and watch and why?

What’s the canon today? For a sense of spiritual history see Jonathan Demme’s BELOVED. For genre excitement see Prince’s SIGN O THE TIMES. See D.W. Griffith’s INTOLERANCE because nothing else is better.

SIGN O THE TIMES (Prince, USA 1987)

Mr. White, thank you for taking the time and answering our questions!

And thank you, Oliver and Marco, for being interested.

Oliver Nöding & Marco Siedelmann

Ein Kommentar zu "reden über schreiben über film(e): #11 armond white (engl version)"

Trackbacks für diesen Artikel